Most people think becoming “financially secure” is some dollar amount in their bank account.

But in my personal experience, true financial freedom comes from understanding finance.

For this reason, my entire concept of the Great Game of Private Capital is designed to help everyday investors develop the knowledge, experience, and abilities needed to take control of their financial future.

But in order to play this game, we have to talk about something most people have little to no understanding of…

Investors and Bankers play two different games with two sets of rules. Investors play by the Banker’s rules, and Bankers (to certain degree) play by their own rules.

And to no surprise, the deck is stacked in favor of the Bankers.

In today’s issue, we’re going to lay the foundation of general wealth creation by understanding the role Bankers play in the world of Private Capital.

Let’s dive in,

-Jake Hoffberg

The Bankers Code to Getting Rich the Easier Way

Generally speaking, there are two main reasons people invest:

Money Now: the investor is looking to increase short-term cash flow to cover living expenses and lifestyle

Money Later: the investor is looking to increase net worth, which in reality, is just cash flow at a future date

Bankers (i.e., “Insiders”) want their Money Now. But the general public (i.e., “Outsiders”) has been conditioned by financial institutions to buy, hold, and otherwise hope for Money Later.

So how do Bankers create Money Now, more commonly called cash flow?

In one word: Arbitrage

To create an arbitrage opportunity, you need to have the following criteria in place:

An income-producing asset (such as an operating business, real estate, insurance policy, and bonds)

A lender that is willing to lend against the asset as collateral, in order to obtain leverage

Income that is larger than the loan payments and expenses related to the asset

This, in a nutshell, is the secret to passive income.

But the devil is always in the details. Namely, collateral and leverage.

We’ll get into both of these terms in just a second, but first…

Imagine a game where there are three types of Players:

Consumers buy products and services. They are constantly being conditioned by Producers and Bankers to “borrow and buy.”

Producers provide products and services and create jobs for Consumers. Producers focus on building systems that generate profit, do all the work, take the greatest amount of risk, and get paid last.

Bankers finance payments between Consumers and Producers. They make the most money, while taking the least amount of risk and get paid first!

[Note: We will also consider non-bank lenders – like fund managers – as Bankers in this game.]

Just like in the game of Monopoly, the Banker has all the money in the game, and they are the ones who “deal” it out.

Banker creates money via lending

Producer borrows money from the Banker

Consumer borrows money from the Banker

Producers and Consumers are forced to work to pay off the debt (i.e., Labor) they owe to the Banker

Banker collects all of the interest, having done no “work” at all. Instead, the money does the work for them.

This means the only way to get money is to borrow it from the bank, with interest.

Here’s an example…

Joe Citizen needs $1,000, so he borrows it from Bob the Banker at 10% interest.

This means Joe agrees to pay Bob the $1,000 he borrowed, plus $100 in interest at a later date.

But if Bob has all the money, where is Joe going to get the additional $100?

Generally speaking, Joe has two choices:

Borrow more money

Work a job for a wage, which can then be used to pay off the debt

We could argue that Joe could become a Producer and turn the borrowed money into a higher form of value (i.e., goods and services)…

But in order to sell those goods and services, because Bob the Banker has all the money, a Consumer will need to borrow money in order to make the purchase, and the cycle continues.

We could argue that Joe could instead become a Producer and turn the borrowed money into a higher form of value (i.e., goods and services)…

But in order to sell those goods and services, because Bob the Banker has all the money, a Consumer will need to borrow money in order to make the purchase, and the cycle continues.

Ultimately, all borrowing costs are eventually passed on to the Consumer.

This, in turn, is tracked by the Federal Reserve as “Household Debt Service Payments as a Percent of Disposable Personal Income”

However, the question still remains: Where does that $100 of interest come from if the Banker has the only $1,000 in existence?

Well, that all depends on the rules of the monetary system.

Representative Money: Currency is backed by a physical commodity such as precious metals or instruments such as checks and credit cards.

Fiat Money: Currency is considered legal tender and backed by a nation’s government, and is not convertible as there is no underlying commodity backing it.

Under a Representative system, the supply of money can only be increased if more of the underlying commodity is deposited into the system…

Or, each unit of currency will be worth less due to devaluation.

Therefore, banks would need to hold a significant amount of capital to issue loans if everything needs to be fully backed.

But in a Fiat system, things work a little differently thanks to Fractional Reserve Banking.

Most countries use fractional reserve banking because it is currently the only financial system model that allows banks to earn a reliable profit.

Without the ability to earn money on their assets, banks would have to fund their operations by charging extremely high deposit fees.

Here’s a somewhat oversimplified version of how it works…

Fractional reserve banking permits banks to use funds (i.e., the bulk of deposits) that would be otherwise unused and idle to generate returns in the form of interest rates on new loans—and to make more money available to grow the economy.

Essentially, banks multiply deposits throughout the country by lending money to borrowers, who then deposit the money (plus interest) back into the bank, and then create more loans based on the increased deposits.

This is called the Deposit Multiplier – the maximum amount of money that a bank can create for each unit of money it holds in reserves.

However, the central bank – in America, the Federal Reserve – determines the minimum amount of required reserves the bank must hold to meet any withdrawal requests from depositors.

Either way, that $100 was, in effect, created out of thin air in the form of a loan that must be repaid.

For this reason, money is debt and debt is money.

If you’re already thinking “Wow, this sounds like an excellent business model,” it gets even better.

You see, Bankers hate taking risks. So instead, what they do is make the borrower take on as much risk as possible.

Why? Because banking (which is lending) is about safety.

This is where collateral comes into play.

Often times, not only is the borrower required to pay back the loan with interest, they must pledge an asset as security for the loan, in case of default.

The easiest example we can use to illustrate how this works is Real Estate.

Let’s say you want to buy an income property that costs $100,000.

But if you don’t have $100k in cash – or maybe you do, but don’t want to use all your cash – you have to borrow.

This means you will put some money down (equity) and borrow the rest from the bank (debt).

But the Banker isn’t going to just give you a massive unsecured line of credit. So what do they ask for?

Pledge the asset as security for the loan (called hypothecation).

Assuming the income produced by the property is greater than the debt servicing costs…

Congratulations! You’ve just arbitraged your first spread and now have a positively cash-flowing asset!

Except for one thing. You – the borrower – carry all of the risks while the bank has essentially none.

Not only do you have to deal with being a landlord, but if you don’t make your payments on time, the bank can seize the asset.

But what does the bank have to do for their income?

Simply print a piece of paper that someone else signs – a mortgage – and that becomes an income-producing asset for the bank.

But wait, there’s more!

Because you, the borrower, have pledged your asset in exchange for the loan (in this case, a mortgage)…

The bank can now use that hypothecated collateral to borrow more money (called rehypothecation) and make more loans.

Essentially, through rehypothecation, a lender can use its borrower’s collateral to apply for a loan themselves.

For example, the lender may use an apartment building, offered as collateral for a commercial real estate loan, as collateral for a new loan.

Rehypothecation is legal because it is often agreed to by clients. Clients may have to agree to terms in order to use a service.

For example, when they deposit shares into a specific brokerage account, they may have agreed that the broker may do certain things to those shares.

The same may be said about bank deposits; in order to open a bank account at an institution, the fine print may state that the firm is allowed to manage your funds as they see fit.

In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission restricts rehypothecation to 140 percent of the loan amount. For example, if collateral of $300 is used to take out a loan for $100, $140 may be rehypothecated.

This newly created debt is now what’s called a derivative; in the case of real estate, collectively, these pools of mortgages are called Mortgaged Backed Securities (MBS).

Securities are tradable financial assets; for example, stocks, bonds, options, commodities, and real estate.

Securitization is the process of pooling various types of contractual debt – such as residential mortgages, commercial mortgages, auto loans, credit card debt obligations, or other non-debt assets which generate receivables – and selling their related cash flows to third-party investors as securities.

After combining mortgages into one large portfolio, they can then be divided into smaller pieces based on each mortgage’s inherent risk of default.

These smaller portions then sell to investors, each packaged as a type of bond.

By purchasing Securities, investors effectively take the position of the Banker.

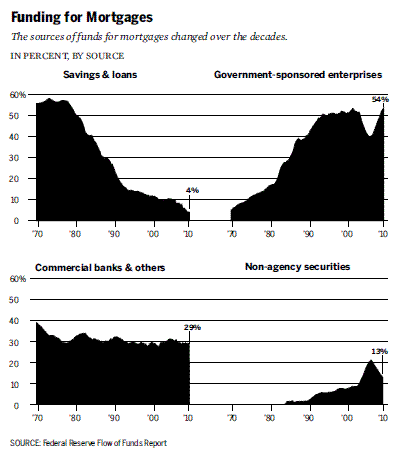

The MBS market emerged as a way to decouple mortgage lending from mortgage investing. Until the 1980s, nearly all U.S. mortgages were held on the balance sheet by financial intermediaries, backed predominately through savings and loans.

Securitization allows these mortgages to be held and traded by investors all over the world. But the U.S. MBS market is one of the largest and most liquid global fixed-income markets, with more than $11 trillion of securities outstanding and nearly $300 billion in average daily trading volume

Securitization is how banks create massive leverage.

Unlike Producers who leverage Other People’s Labor to make money…

Bankers leverage Other People’s Money to make money.

And if you want to learn how to get your money to start working for you, it’s crucial you understand how to play the game like Bankers do.

How retail investors can play the game like Bankers

If Insiders (i.e., Bankers) are masters at shifting risk to Outsides (i.e., Producers and Consumers)…

How do we flip the script and get on the other side of the risk/reward equation?

The key is to become our own Banker and start borrowing money from ourselves.

Instead of borrowing money from the bank, and then paying the bank back, with interest…

Why not borrow money from yourself, and pay yourself the interest instead?

Instead of your interest payments going to pay the salaries and bonuses of an endless army of Bankers, financial advisors, and brokers, who get paid regardless of whether you win or lose…

Why not pay your family instead?

In a nutshell, this is how a Family Office helps build and maintain generational wealth – they act as a Family Bank (among other things).

While technically, you don’t have a bank charter, and therefore aren’t a “real” bank…

The Family Bank is a family-funded entity that provides banking services to family members and family businesses.

Senior family members provide funds to the family bank, which finances next-generation members’ interests, business ventures, education, homes and other assets.

Junior family members should also be encouraged to invest, even a small amount.

If it is designed and managed in a professional and democratized way, this structure can empower next-generation members to build wealth responsibly while pursuing their own interests and passions.

For the sake of landing this plane and getting you to the “but what do I actually do?” part of this email…

Generally speaking, banking consists of seven parts:

Raising Capital: In order to get money, the bank needs to borrow money from someone else – either from individuals and corporations in the form of deposits, or from other banks.

While cash flow may be king, access to cheap sources of capital is the Ace, Joker, Wild Card, and Reverse Uno all rolled up into one.

Remember: Bankers borrow low, lend high, and capture the spread.

Generally speaking, your primary source of capital will be from family members, and most likely, only your household’s wealth, in the beginning of this process.

Asset Allocation: Once you have the capital, now you have to have a plan for what to do with it.

We can’t go too deep into the asset allocation rabbit hole, but there are three components of asset allocation.

First is the Investment Policy Statement – a document drafted between a portfolio manager and a client, that outlines general rules for the manager. In this case, you are the manager, and the family is the client.

This statement provides the general investment goals and objectives of a client, and describes the strategies that the manager should employ to meet these objectives.

Strategic asset allocation could be defined as a collection of long-term decisions determining an investor’s general portfolio structure.

We first discussed how to think about diversifying away from an “all public” portfolio into a “Public/Private” portfolio here.

Here’s the Tiger 21 Member Allocation for quick reference

Tactical asset allocation, on the other hand, can be described as the short-to-mid-term realization of those decisions.

This includes individual stock selection, reactions to market shocks, or otherwise opportunistic investments.

Origination: Now that you have a plan, you need to go find opportunities to put said money into.

You can either look for opportunities in the public stock market, of which there are thousands of ticker symbols for you to choose from.

Or, you can look in the private capital markets – for example, on alternative investment platforms like Equifund.

Underwriting: Once you originate an opportunity, now you need to perform due diligence.

This is the process of understanding the risk, pricing that risk, and setting the terms and conditions for lending.

If you are a small balance investor participating in a private round of financing, chances are, you will not be able to directly negotiate the terms of the deal. Instead, the opportunity is “packaged” and the terms are the terms and the price is the price.

However, if you are doing any sort of intra-family loan or otherwise doing your own deals, you would have a greater ability to negotiate the price and terms with the Borrower.

Financing: Assuming the opportunity meets your criteria, now it’s time to write a check!

For the sake of simplicity, this means purchasing a financial product of some kind (i.e., stocks, bonds, mutual funds, ETFs, private equity, private credit, real estate, currency, life insurance, and annuities, ).

Asset Location: Once that asset is acquired, it has to be held inside some sort of account (or “vehicle”).

Chances are, you probably have a variety of bank accounts, brokerage accounts, retirement accounts, and other accounts from which money can be invested.

These accounts are either taxable, tax-advantaged, or tax-deferred.

Depending on a variety of factors, it will make more sense to hold certain assets in certain accounts.

Asset Management & Trading: Last but not least, the asset has to be managed in an effort to produce positive returns, all while managing risk

These are all the decisions you’ll have to make AFTER you’ve purchased the asset.

Remember: Bankers ARE NOT in the risk-taking business. They are in the money business.

The only reason they finance the purchase of a building is for the sake of creating a spread. The same logic applies to owning an operating company.

Most people think buying a business is about the business. In reality, it’s irrelevant what the business does, only that it can be used as collateral to generate a spread.

Why? Because Bankers play the finance game.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting you never buy equities and never take risk.

But there’s a difference between taking a small portion of your overall portfolio to finance high-risk / high-reward opportunities…

And putting all your money on black and seeing what happens.

That difference is risk management.

As a reminder, all investing carries some form of risk. Especially if you are investing in privately held companies.

With that said, it’s occasionally the private markets where the best risk-adjusted returns are found.

And as the famous quote from Shakespeare’s Hamlet goes “Ay, there’s the rub.”