Now that the annual debt ceiling shakedown seems to be coming to its natural conclusion of a last minute deal…

The “de-dollarization” narrative is picking up steam as countries start reducing USD reserves, increasing gold reserves, and striking new trade deals to settle in NOT dollars.

Combine that with the mounting national debt the U.S. has, the many articles on how bad it would be if the U.S. defaulted on this debt, and attention-seeking “experts” on Twitter…

And welcome to the latest episode of “The Death of the Dollar” (which has been around since basically the 70s).

Personally, I think this narrative is complete nonsense.

And that’s why today, we’re going to take a slight departure from our normal “Weekend Edition” format, and talk about how the current world order came into existence…

Why the globalized economy is wildly dependent on America and the deep liquidity provided by the U.S. dollar…

And how gold fits into the broader macroeconomic environment as well as foreign policies.

Let’s dive in,

-Equifund Publishing

The Gold Bull Market in Every Currency (Except USD)

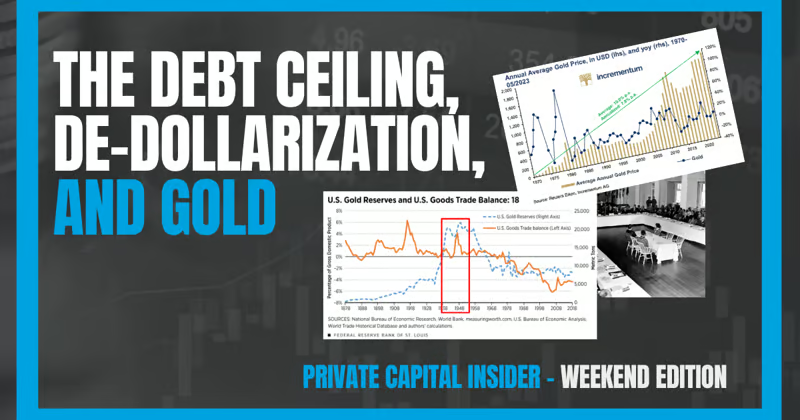

In case you missed it, research group Incrementum released their 2023 edition of “In Gold We Trust” – the “gold standard” report about all things gold (and by extension, macroeconomics and monetary policy).

For those of you who don’t have time to read all 417 pages of the report, I did, so you don’t have to.

Here’s one of the most important things you need to understand about gold: In every single major currency – except the U.S. dollar – gold has marked new all-time highs since the outbreak of the Ukraine war.

Flipping back even further in the history books, since the “IPO of gold” on August 15, 1971, the average annual increase of the gold price in U.S. dollars amounts to 10.0%, with an annualized growth rate of 7.8%.

While there’s no shortage of “hard money” advocates who will say that the day Nixon closed the gold window was sacrilegious, and opine for the return to the gold standard…

Most people have a very shallow understanding of how monetary systems work (and the challenges they have at scale under an asset-backed regime).

For that, we have to go back to the birth of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

The Big Idea

Bretton Woods and The Birth of King Dollar

On July 1, 1944, 730 delegates from the forty-four Allied nations and their respective colonial outposts convened at the Mount Washington Hotel in the skiing village of Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, with a mission to do nothing less than decide the fate of the postwar world.

After World War II, these countries saw the opportunity for a new international system that would draw on the lessons of both the previous gold standards and the experience of the Great Depression, and provide for postwar reconstruction.

It was an unprecedented cooperative effort for nations that had had barriers between their economies for more than a decade.

They envisioned an international monetary system that would ensure exchange rate stability, prevent competitive currency devaluations, and promote economic growth.

During the conference, the delegates agreed to establish two new institutions:

- The International Monetary Fund (IMF) would monitor exchange rates and lend reserve currencies to nations with balance-of-payments deficits.

- The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, now known as the World Bank Group, would be responsible for providing financial assistance for the post World War II reconstruction, and the economic development of less developed countries.

Not only did these institutions help knit the devastated Europe back together, and otherwise set the foundations of the globalized free trade economic system that endures to this day.

It was the beginning of the world’s singular reserve currency: The U.S. Dollar.

Or at least, that’s the story you’ve probably heard in history books.

What really happened behind closed doors – and what was really responsible for today’s global economic system – was the creation of the most extraordinary foreign policy of all time.

At Bretton Woods, delegates fully expected to hear the details of a Pax Americana: a global American imperial system comprised of what was left of the previous European Empires.

But what the Americans proposed shocked everyone.

Instead of a new world order occupied by American boots on the ground, along with the tariffs, taxes, and quotas familiar to the imperial system of yore…

They proposed a global “Free Trade” system in which the United States’ Navy would provide full security for ALL maritime trade, bar none, at their own cost, with full access to the largest consumer market in human history.

What did the Americans want in return for the opportunity to partner with the only possible consumer market, the only possible capital source, and the only possible guarantor of security?

History’s greatest military alliance… to arrest, contain, and beat back the Soviet Union from spreading communism to the developing world.

Accepting the deal was a no-brainer. None of the Allies had any hope of economic recovery, or maintaining their independence from the Soviets, without massive American assistance.

And just like that, thanks to this seemingly absurd foreign policy that promised to do nothing less than indirectly subsidize the economy of every country represented at the conference…

The Americans founded the greatest alliance in history, surrounded the Soviets with a thick hedge of hostile countries willing to serve as the Americans’ first line of defense against the Red Army, all without firing a single shot.

For the first time in recorded history, the entire “free world” was open for business.

With the Americans now personally guaranteeing safe passage for all maritime trade, the Bretton Woods members were now allies, freed from the need to defend against centuries-old rivalries.

Goods, Services, and Money:

A Brief Primer on Monetary Policy and Trade Deficits

As a general consideration, in order to facilitate a stable, global free-trade system, the number one thing you DO NOT want is for the value of currencies to be volatile.

Here’s why…

The sustainability – and, indeed, the very survival – of the global economic ecosystem is notpredicated on the balance of currency… but on the delicate balance between real production and real consumption of real goods and services.

This means if the US’s exportable supply of goods and services increases relative to the demand for importable goods and services from its trading partners, one of two things needs to happen:

- Prices of exports would need to fall relative to the price of imports, or

- A balancing mechanism was needed to account for the growing deficit between countries

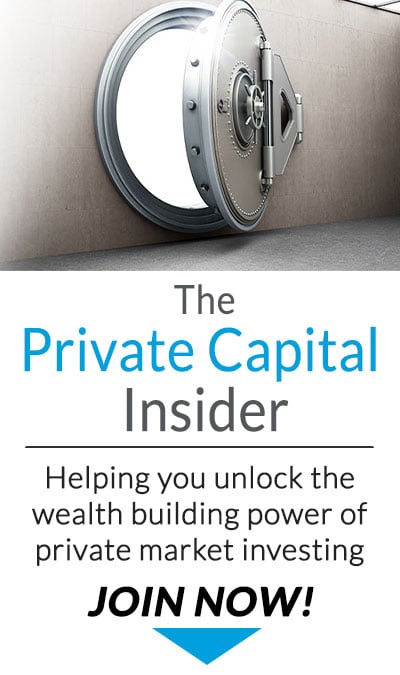

For the most of human history, gold was the balancing mechanism of choice. But now that the U.S. controlled ~70% of the gold reserves, it was now the U.S. dollar.

In addition, now that the U.S. was the only industrial, monetary, and military power left standing, this created a bit of a problem in terms of balancing goods and services between countries.

This meant the U.S. was, by default, running a massive trade surplus (as no other nation had the ability to export goods into America).

To fix the problem, the U.S. would have to reverse the imbalances in global wealth by running a balance of trade deficit, financed by an outflow of U.S. reserves to other nations (i.e., a financial account deficit).

From 1948 to 1954 the United States provided 16 Western European countries with $17 billion in grants.

Aid to Europe and Japan was designed to rebuild productivity and export capacity, thereby bringing the Balance of Payments into equilibrium at some point in the future.

However, the benefits of owning the global reserve currency came with a price…

The United States would need to print increasingly more dollars, and run ever growing deficits to facilitate global trade – an act that is inherently inflationary, and would eventually undermine the confidence in the reserve currency.

More specifically, as the supply of USDs expanded – unless the supply of physical gold also expanded – there would eventually be a “bank run” on the United State’s supply of physical gold.

This quandary is known as the Triffin Dilemma, named after Robert Triffin, an economist who wrote of the impending doom of the Bretton Woods system in his 1960 book, Gold and the Dollar Crisis: The Future of Convertibility.

The Impossible Trinity, The Triffin Dilemma and the End of Bretton Woods

Chronic deficit in the balance of payments meant that the number of dollars abroad far exceeded the U.S. gold reserve.

As the trade imbalance increased, confidence in the dollar dropped, and the U.S. began to lose its dominant position in global production and international trade.

To fix the situation, the U.S. would either need to reduce the supply of currency in circulation by trading gold for dollars…

Or, they could decide to change the rules of money.

As far as a central bank is concerned, this means controlling three things:

- Fixed foreign exchange rate: the value of your currency in relation to some other currency is pegged at a fixed rate

- Free capital flow (i.e., the absence of capital controls like tariffs and taxes): the ability of investors to get their money in and out of a country quickly and easily

- Sovereign monetary policy: The ability to set interest rates without regard for what other central banks are doing

Known as the Impossible Trinity (or “Trilemma”), the economic concept states that a central bank can only pursue two of the above-mentioned three policies simultaneously.

As stated by Paul Krugman in 1999:

The point is that you can’t have it all: A country must pick two out of three.

It can fix its exchange rate without emasculating its central bank, but only by maintaining controls on capital flows (like China today);

it can leave capital movement free but retain monetary autonomy, but only by letting the exchange rate fluctuate (like Britain – or Canada);

or it can choose to leave capital free and stabilize the currency, but only by abandoning any ability to adjust interest rates to fight inflation or recession (like Argentina [in 1999], or for that matter most of Europe).

This brings us back to the United States and the Triffin Dilemma.

Under the Bretton Woods Accord, foreign currencies are pegged to the U.S. dollar at a fixed exchange rate.

Thanks to Executive Order 6102 signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, the dollar was pegged to gold at a fixed exchange rate of $35.00 per ounce.

In the Bretton Woods world, this meant that no physical gold needed to change hands in order to settle the Balance of Payments, only U.S. Dollars, which are redeemable for gold by a country’s central bank.

However, this means the United States had a huge advantage. The government could effectively settle its debts using its own currency – which it can print at effectively no cost – instead of real goods and services being payable in the form of physical gold.

The French would later call the dynamic “America’s Exorbitant Privilege.”

Thanks to this privilege, the United States was largely able to avoid the consequences of the Impossible Trinity.

Why? Because the U.S. was so large compared to its trading partners – and its central bank can effectively print unlimited money with limited consequences – it could easily defend the dollar peg to gold.

In many ways, America was able to export inflation to other countries because of the high demand for dollars.

But according to the Triffin Dilemma, as the reserve currency continues to expand, countries which previously held the currency in lieu of gold in their official reserves may no longer be willing to do so.

If that happens, the reserve currency risks collapse via a “bank run” on gold.

At the same time, if the reserve country takes measures to reduce the outflow of its currency via capital controls, this may starve the system of needed liquidity… which in turn, will almost certainly cause a market crash.

Thus, a system where a country’s currency coexists with gold as official reserves requires additional safeguards to ensure its stability.

Enter, the London Gold Pool.

As we already know from the Impossible Trinity, defending the Dollar-Gold peg requires a trade off. Unless the United States was willing to abandon its Sovereign Monetary Policy, the central bank had two options.

- The fixed exchange rate would need to be sacrificed and be allowed “float” thereby ending Bretton Woods, or…

- The free market price of gold would need to be maintained near the official $35 per ounce price set by the United States by implementingcapital controls.

Not surprisingly, the latter was a far preferable choice to the former.

Late in 1960, amidst US presidential election debates, panic buying of gold led to a surge in price to over $40 per oz; The United States sought means of ending the drain on its gold reserves.

In November 1961, a group of eight central banks formed the London Gold Pool in an effort to regulate the price of gold and defending the $35/oz price.

For this purpose each nation provided a contribution of the precious metal into the London Gold Pool, led by the United States pledging to match all other contributions on a one-to-one basis, and thus contributing 50% of the pool.

The way the pool was to work was that the Bank of England (BOE) would supply physical gold as needed into the public marketplace whenever the price started to rise. The BOE would then be reimbursed its gold from the pool according to each countries agreed percentage.

If the price of gold fell below $35 an ounce, the pool would buy gold, increasing the size of the pool and each member’s stake accordingly.

However, from 1950 to 1969, as Germany and Japan recovered and their manufacturing capabilities grew, the US share of the world’s economic output dropped significantly, from 35% to 27%.

Furthermore, a negative balance of payments, growing public debt incurred by the Vietnam War and monetary inflation by the Federal Reserve caused the dollar to become increasingly overvalued in the 1960s.

In turn, this caused countries to begin converting dollars into gold, draining the US Treasury of its reserves. In 1967, France publicly withdrew from the London Gold Pool and was aggressively repatriating US dollars to America to obtain physical gold.

When the United Kingdom devalued the pound by 14.3% on November 18th, 1967, that further accelerated the run on physical gold reserves held in the London Gold Pool.

Late on Thursday, March 14th, 1968, the US government asked the British government to close the London Bullion Market the next day as an effort to stem demand for gold. British Queen Elizabeth II petitioned the House of Commons to declare March 15th, 1968 a bank holiday.

The following Monday, the United States Congress passed a law repealing the requirement that the US Treasury maintain a gold reserve to back the dollar; this would shortly lead to the collapse of the London Gold Pool and the end of Bretton Woods.

In August 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon announced the “temporary” suspension of the dollar’s convertibility into gold and closing the gold window.

An attempt to revive the fixed exchange rates failed, and by March 1973 the major currencies began to float against each other.

Since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, IMF members have been free to choose any form of exchange arrangement they wish (except pegging their currency to gold).

These arrangements include allowing the currency to float freely, pegging it to another currency or a basket of currencies, adopting the currency of another country, participating in a currency bloc, or forming part of a monetary union.

And now, as we see the supposed threat of the BRICS countries seeking to de-dollarize – alongside whatever chimera of a currency Russia-China comes up with backed by commodities, oil and gold…

I remain unconvinced that any currency poses any threat to the dollar dominance, unless they are willing to replace America as the security guarantor for global trade.

Why King Dollar Is Here to Stay (and gold could still go higher from here)

Every single year for as long as I’ve been in the markets, I’ve seen stories about the demise of the dollar and the end of the American empire.

Chances are, you’ve probably seen this misleading chart that all but predicts that the U.S.dollar is at or nearing the end of its ~100 year reign as the global reserve currency… Similar to the U.K., France and others before…

And you’ve seen the very scary charts about the national debt that continues to climb at alarming rates.

The national debt is now USD 31.4 trillion, or 121% of GDP.

Guess what? So is everyone else (especially China)!

On a relative basis, America – and the USD – is still the “best house in a bad neighborhood.”

As Warren Buffet recently said “Despite some severe interruptions, our country’s economic progress has been breathtaking. Our unwavering conclusion: Never bet against America.”

What does any of this have to do with gold you might ask?

If you believe – like I do – that the Commodity Supercycle thesis is underway, geopolitical tensions will continue to rise, inflation is inevitable, and a recession is near…

If that doesn’t sent gold prices up, I don’t know what will.

Have a great weekend!