According to Chairman Ann Wagner’s opening remarks…

“This hearing will examine the ways in which Congress can give main street investors better access to investment opportunities that have been historically available for only the wealthy or highly educated.

Congress must work to expand opportunities for all investors and entrepreneurs in the securities markets in order to create long-term, sustainable growth within our economy.

To increase investment opportunities for all Americans and help entrepreneurs raise more funds, we must broaden the pool of investors in our private markets.”

Why should you care? Because if you’re interested in diversifying your portfolio out of the public markets and into the private markets, there’s one question you’re going to be asked over and over again…

Are you accredited or unaccredited?

For decades, the answer to this question was determined by your income and net worth, with very few exceptions.

But thanks to new regulations – and growing political support to expand retail access to private markets – pathways towards accreditation are emerging based on your knowledge and sophistication level.

That’s why today, we’re going to talk about what an accredited investor is, why these investor protections exist in the first place, and the emerging pathways to accreditation for those that don’t normally qualify.

Let’s dive in.

A Brief History of Investor Protection & Accredited Investor Regulations

Historically, buying investment products (called “Securities”) was limited to only the wealthy. It was believed that because of their wealth, they could handle the high risk – and the high potential for loss of principal and even fraud – that came with investing.

However, as the importance of the stock market grew, it became a larger influence on the overall economy.

Eventually, as people started earning higher disposable income, more people could afford to purchase securities and otherwise invest.

In theory, these investors were protected by something called “Blue Sky Laws” – a term said to have originated in the early 1900s, gaining widespread use when a Kansas Supreme Court justice declared his desire to protect investors from speculative ventures that had “no more basis than so many feet of ‘blue sky.’”

But without any real regulatory oversight, it did little to protect investors from companies that issued securities (called “Issuers”), promoted real estate opportunities, and other investment schemes while making lofty, unsubstantiated promises of greater profits to come.

By the 1920s, the economy was “roaring” along, and people were desperate to get their hands on anything to do with the stock market.

To make matters worse, many investors began using a new tool called “margin” to use their existing stocks as collateral to borrow money from their broker and invest in more stocks.

Stock prices went up nearly 10 times as ordinary individuals bought stock, often for the first time.

With so many uninformed investors jumping into the speculative craze… brokers, market makers, and even bankers started manipulating the markets to drive prices higher before dumping their shares on the unsuspecting public.

Then, on Oct 29th, 1929, “Black Tuesday” – the largest one-day drop in stock market history – sent the country spiraling into the Great Depression.

It is estimated that one-half of the $50 billion in new securities offered during this period became worthless, and restoring investor faith in capital markets was essential to economic recovery.

So, as the government does, they decided to hold hearings and figure out who to blame.

In 1932, the U.S. Senate Banking Committee began a much-publicized investigation of the nation’s financial sector known as the “Pecora hearings.”

These hearings revealed how the country’s most respected financial institutions had knowingly misled investors, acted irresponsibly, and participated in widespread insider trading.

The hearings lead Congress to pass the Securities Act of 1933 (the “Securities Act”), the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”), and eventually the Investment Company Act of 1940 (the “40 Act”).

These three acts provide the framework for the oversight and regulation of the securities markets through disclosure, recourse, and enforcement.

Often referred to as the “truth in securities” law, the Securities Act has two basic objectives:

- To require that investors receive financial and other significant information concerning securities being offered for public sale; and

- To prohibit deceit, misrepresentations, and other fraud in the sale of securities.

In order to enforce these new disclosure requirements, the Exchange Act created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) – an independent federal agency led by a bipartisan, five-member Commission whose mission is “to protect investors, maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets, and facilitate capital formation.”

As part of this new regime, all Issuers seeking to sell new securities in the public markets would now be required to disclose important financial information through the registration of those securities.

Said another way, in order to raise capital, Issuers had to undergo an initial public offering (IPO) and assume all the costs that come with being a publicly listed company.

However, Congress also recognized that in certain situations there is no practical need for registration or the public benefits from registration are too remote.

For this reason, the SEC allows businesses to raise capital in the private markets using different exemptions; as the name suggests, this exempts the issuer from the registration requirement.

The most commonly used exemption used by Issuers is called Regulation D (or “Reg D”).

Reg D is composed of various rules – Rule 501, 502, 503, 504, 505, and 506 – prescribing the qualifications needed to meet exemptions from registration requirements for the issuance of securities.

Rule 501 of Regulation D provides the definition of who is eligible to purchase securities under this exemption (called an “accredited investor”). To qualify, you must meet one (or both) of these criteria…

- A natural person with income exceeding $200,000 in each of the two most recent years, or joint income with a spouse exceeding $300,000 for those years and a reasonable expectation of the same income level in the current year.

- A natural person who has an individual net worth, or joint net worth with the person’s spouse, that exceeds $1 million at the time of the purchase, excluding the value of the primary residence of such person. The home exclusion part was adopted by the SEC in 2011.

It is “intended to encompass those persons whose financial sophistication and ability to sustain the risk of loss of investment or ability to fend for themselves render the protections of the Securities Act’s registration process unnecessary.”

For the sake of brevity, we won’t go into the other Rules of Reg D. But the key takeaway here is this:

If you as an individual don’t qualify as an accredited investor, you cannot invest in any company using the Reg D exemption to raise capital.

For the ~90% of American households who do not qualify as accredited investors, this represents a serious obstacle.

“From July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022, more money was raised under [Regulation D] Rule 506(b) ($2.3 trillion) than by all registered offerings ($1.2 trillion).

Even offerings under [Regulation D] Rule 506(c) offerings, a much less often used exemption, raised more money ($148 billion) than was raised in IPOs ($126 billion).”

To put this in context, this means the vast majority of Americans who are unaccredited investors – and thereby limited to the public market – had access to ~3% of the securities (by dollar value) made available in the private market.

And over the past several years, we’ve seen continued support from politicians and regulators seeking to broaden access to this private market.

In 2020, the SEC extended accredited investor status to natural persons who hold certain professional credentials and who are “knowledgeable employees” of the issuer of the securities being offered or worked within the securities industry.

Under this small expansion, individuals with the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority Inc.‘s (FINRA) Licensed General Securities Representative (Series 7), Licensed Investment Adviser Representative (Series 65), and Licensed Private Securities Offerings Representative (Series 82) certifications qualify as accredited investors.

And after the most recent February 8th hearings, there’s a battery of new proposed bills seeking to expand access – all of which will likely be wrapped into the JOBS Act 4.0 proposal.

- Amend the Accredited Investor Definition (Proposed Bill H.R. 3328). Codify the definition of “accredited investor” to include certain licenses or possessing qualifying education or experience, thus expanding investment opportunities for sophisticated-but-not-yet-wealthy investors and providing private companies with additional sources of funding.

- Formalize Investor Education (Proposed Bill H.R. 4776). Direct the SEC to create an examination that individuals can take to be certified as an accredited investor, as well as provide investor training for any individual who is certified as an accredited investor through an examination established by the Commission.

- Require Additional Certifications (Proposed Bill H.R. 4708). Require SEC to incorporate additional “certifications, designations, or credentials that further the purpose of the accredited investor definition” within 18 months, and thereafter assess the addition of certifications, designations or credentials every 5 years.

- Require Self Certification (Proposed Bill H.R. 4753). Require the SEC to create a form that would allow for individuals to certify that they are sophisticated and understand the risks of investment in private offerings.

While there is certainly some opposition to these proposals, it is possible some version of these reforms will be passed in 2023/24.

Why? According to the Wall Street Journal…

“Private-equity firms, particularly publicly traded ones, must continue to add assets under management in order to earn more fees and satisfy their shareholders.

The biggest firms over the years have become sprawling enterprises with businesses that invest in real estate, credit, infrastructure and more.

Their traditional customers, such as pensions and other institutional investors, have largely stopped putting more of their portfolios into private markets.

Firms are now counting on wealthy individuals for their next leg of growth.”

As Wall Street firms continue to search for growth, it doesn’t seem far-fetched to suggest there is a vested interest for Big Finance to expand retail access to private markets (you can read more about our thoughts on this here).

And for investors interested in participating in private market opportunities, it’s important to understand how these securities are structured and the risks that come with them.

How to Prove Accredited Investor Status on Equifund

As you may already know, the JOBS Act introduced the Reg CF and Reg A+ exempt offering frameworks.

These frameworks allow for both accredited and unaccredited investors to participate in private market offerings (albeit with some restrictions).

However, we are getting more requests to see more Reg D offerings on the Equifund portal – by law – would be open to accredited investors only.

Please note, Equifund is not an Underwriter nor a registered Broker/Dealer. Any Reg D offerings listed on the Portal are underwritten by a firm actively registered with the SEC and FINRA.

If you are an accredited investor – and you’d like to get your Equifund profile set up correctly to invest in Reg D offerings – here’s how to do that.

For Individuals

Step 1) Update Your Accreditation Status.

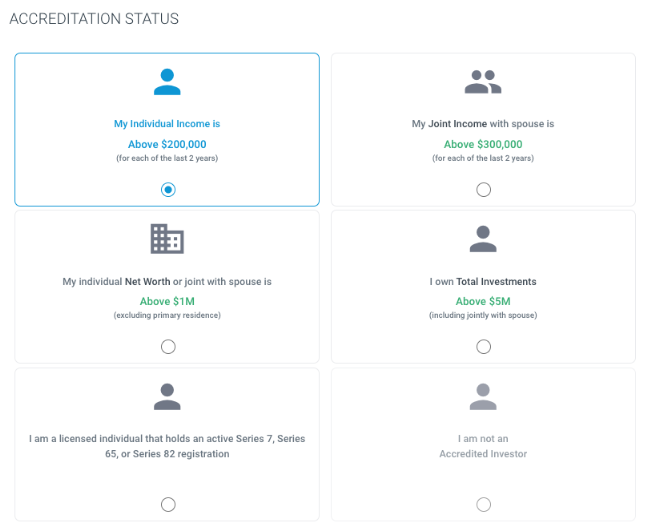

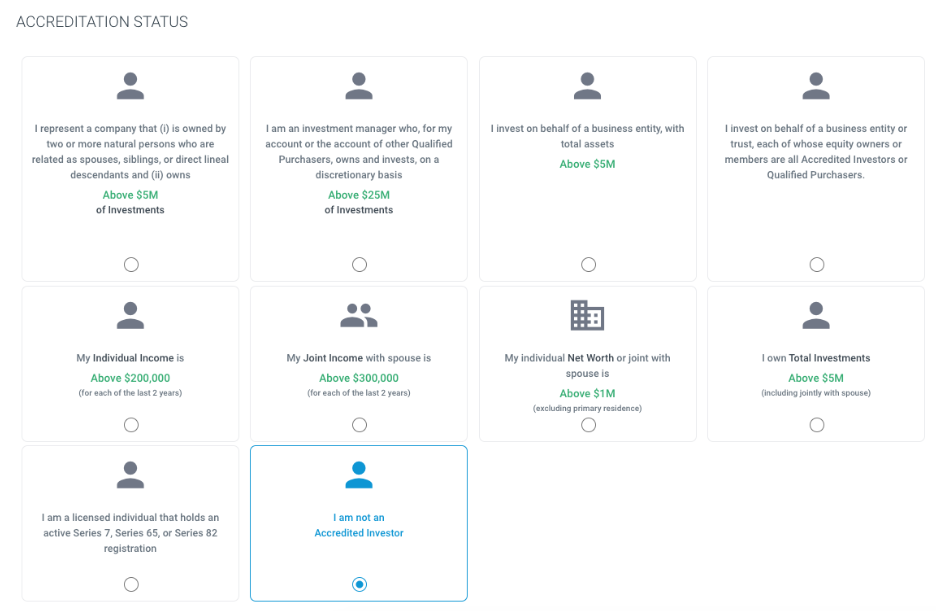

Inside your Equifund profile, there is a tab called “Accreditation” where you’ll see the following six options:

All you need to do is select which one best fits your description.

You won’t need to upload any documentation until you place an order via a Reg D offering. Once you do, you will be asked to upload documentation during the checkout process.

For more information on the SEC’s Net Worth Standard, please read their article on the topic here.

Step 2) Upload Documentation During Checkout

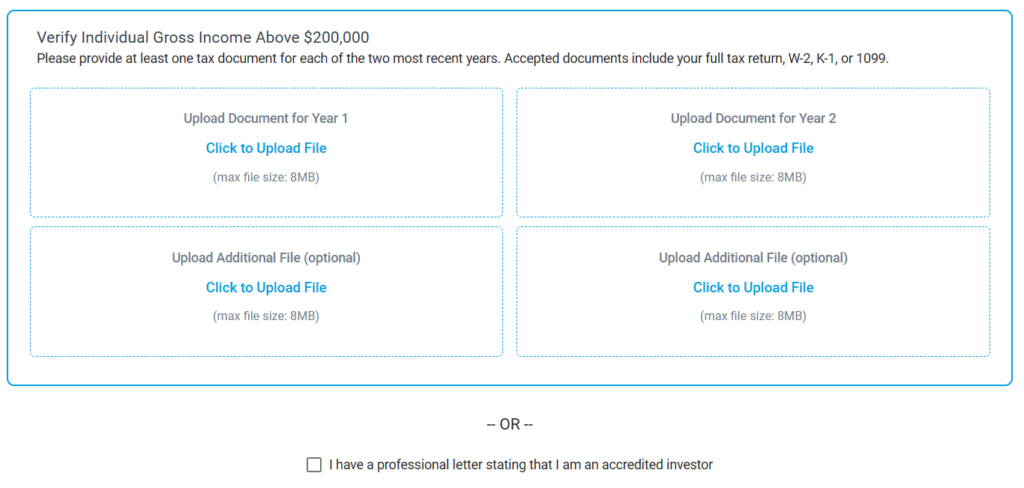

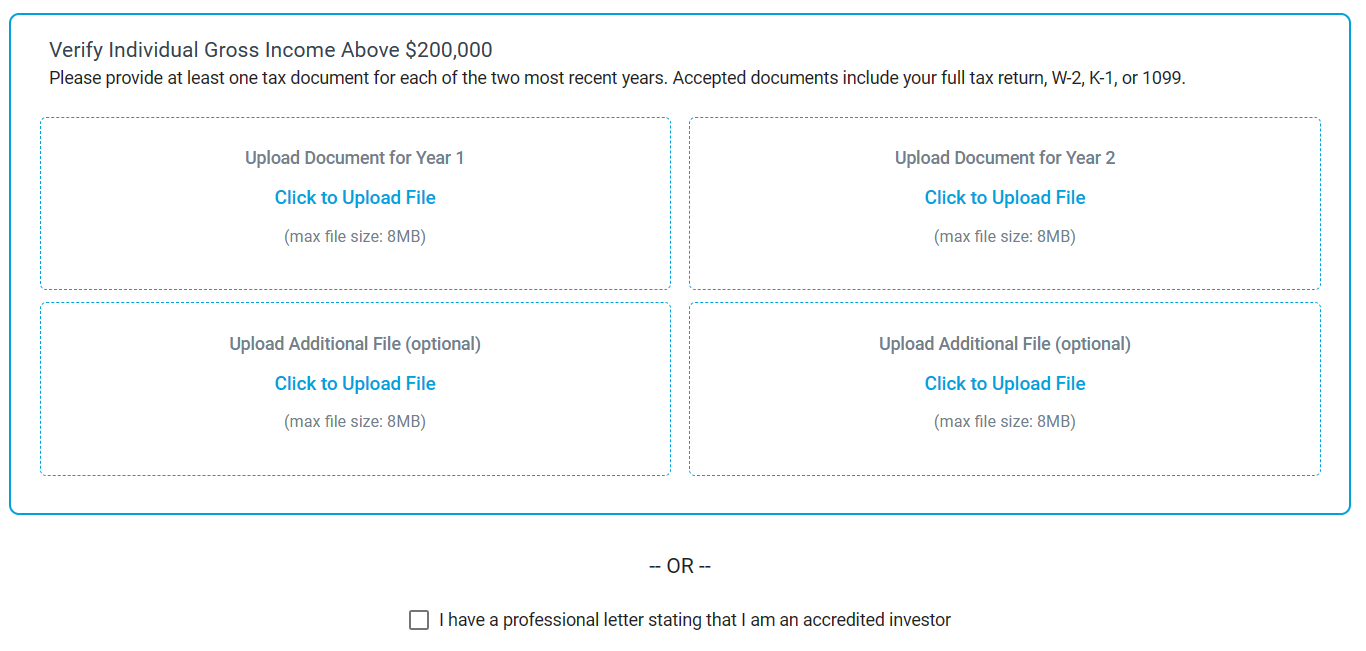

During the checkout process, you will be asked to confirm how you qualify as an accredited investor. Then you will be given three options for proving it.

First… you can upload your full tax returns, W-2, K-1, or 1099 for the previous two years.

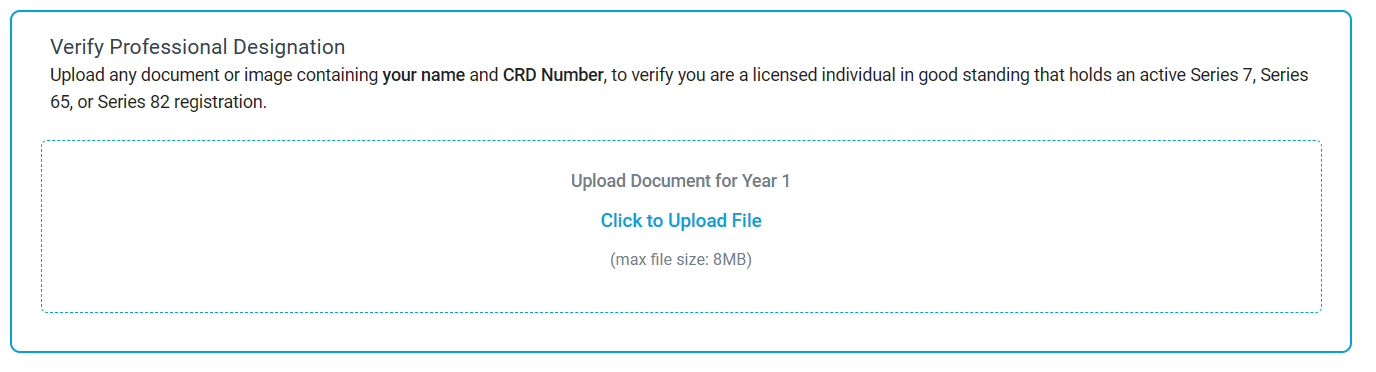

Second… if you qualify under one of the licensing requirements, you can upload documents verifying you are in good standing.

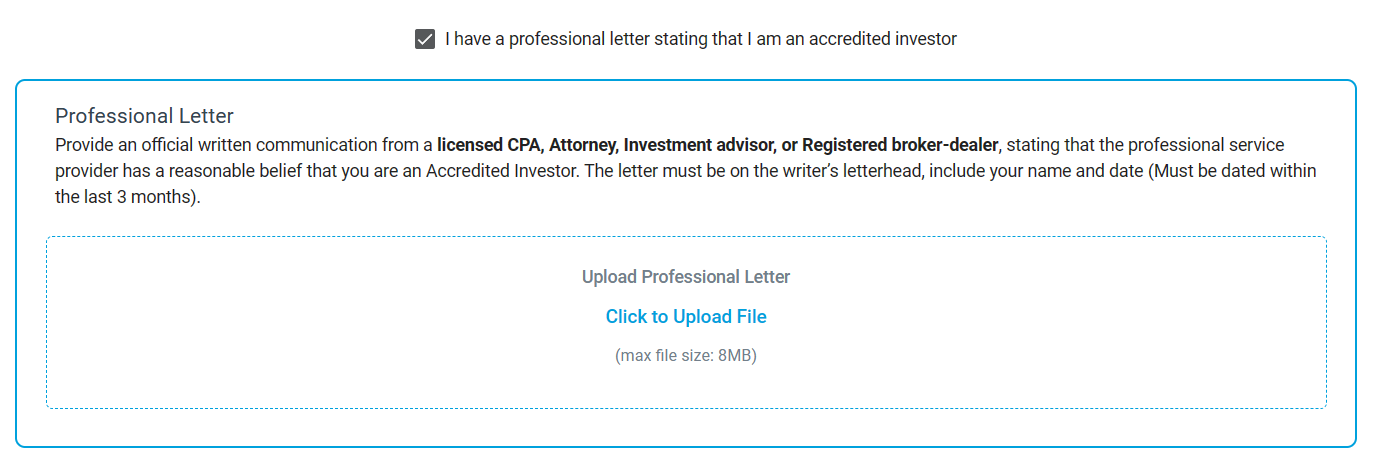

Third… you can get a “Professional Letter” from a licensed CPA, attorney, investment advisor, or registered broker-dealer stating they believe you to be accredited.

For Corporations & Trusts

Step 1) Update Your Accreditation Status.

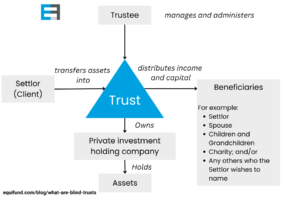

If you are investing as an entity – most commonly an LLC or a Trust – you have similar options as an individual, but also a few additional ones.

Here is what the selection screen looks like:

Any entity in which all of the equity owners (or grantors in the case of a trust) are accredited investors is also accredited. The same goes for any trust with assets that exceed $5 million in total. However, the trust or entity must not be formed for the specific purpose of purchasing securities.

Please note that – in addition to your accreditation verification – we will also need to collect any and all required AML/KYC documentation for the entity in question.

Step 2) Upload Documentation During Checkout

During the checkout process, you will be asked to confirm how you qualify as an accredited investor. Then you will be given three options for proving it.

First… you can upload your full tax returns, W-2, K-1, or 1099 for the previous two years.

Second… if you qualify under one of the licensing requirements, you can upload documents verifying you are in good standing.

Third… you can get a “Professional Letter” from a licensed CPA, attorney, investment advisor, or registered broker-dealer stating they believe you to be accredited.

Yours for investing equality,

Jordan Gillissie – CEO

Equifund